My Parents Only Wanted What was Best for Me. Too Bad They Had No Idea What It Was.

When I was a teenager, I was an exchange student in Australia — and it changed the trajectory of my life.

I stood at the top of Wattamolla Cliff in Australia, peering over the edge at the water thirty feet below.

Should I jump?

I’d been standing here fretting for at least twenty minutes, trying to work up the nerve to do just that. But it was three times higher than any jump I’d ever made before — and it scared the shit out of me.

Everyone else had already jumped — mostly, the other kids in the exchange program that had brought me to Sydney, Australia, for my senior year of high school. They waited in the water below, gently encouraging me to go for it.

I wanted to make the leap, but I was utterly terrified. I didn’t take risks like this. What if I landed wrong and hurt myself? What if I did the belly-flop heard around the world?

It felt like a test. Had my time in Australia changed me as much as I’d wanted when I’d first arrived? My stay as an exchange student was almost over, and if I didn’t jump now, it would feel like I’d failed that test.

I took a breath, stepped forward — and promptly spun back around, far away from the edge.

Need travel or international health insurance? We recommend Genki or Safety Wing. For a travel credit card, get 60,000 free miles with Chase Sapphire Preferred. Using these links costs you nothing and helps support our newsletter.

It’s the biggest travel cliché of all, how travel changes a person — makes them more confident and open-minded. Happier.

After five years of traveling the world as a digital nomad, I can happily attest that this is true. I know I’ve changed for the better.

However, not all travel is equally transformative. My time as a nomad has been fascinating and enriching. But living in Australia turned me into a completely different person — and maybe even saved my life.

At the very least, it saved me from a life that would’ve been horribly wrong for me.

Even now, I know my parents only wanted the best for me. Or what they thought was the best for me.

Unfortunately, that meant endlessly discouraging my dreams of becoming a writer, which they saw as a road to instability and poverty.

My mother pushed me to study the law, ostensibly because I liked to argue. My father wanted me to go into banking, his own profession — which, incidentally, he hated, and which always made this seem like such weird advice.

The thought of doing either profession gave me a stomach ache. So did their dreams of my getting married, buying a house in the suburbs, and having kids, though not for reasons I yet understood.

I was also overweight, and my parents wanted what was “best” for me here too.

My father forced me to play football for years, even though I hated it. Whenever my mother and I shopped for the “husky”-sized clothing I had to wear, she made humiliating comments in hopes that would finally prompt me to slim down.

It was 1981, and I was an introverted seventeen-year-old who loved books and hated the bleak future he saw stretched out in front of him — the conventional life he didn’t want. It’s no wonder I overate.

I needed something to knock me off of the trajectory I was on — something to bring about a massive change I couldn’t make on my own.

Where’s an asteroid when you need one? Because I desperately needed something to knock me into an entirely different orbit.

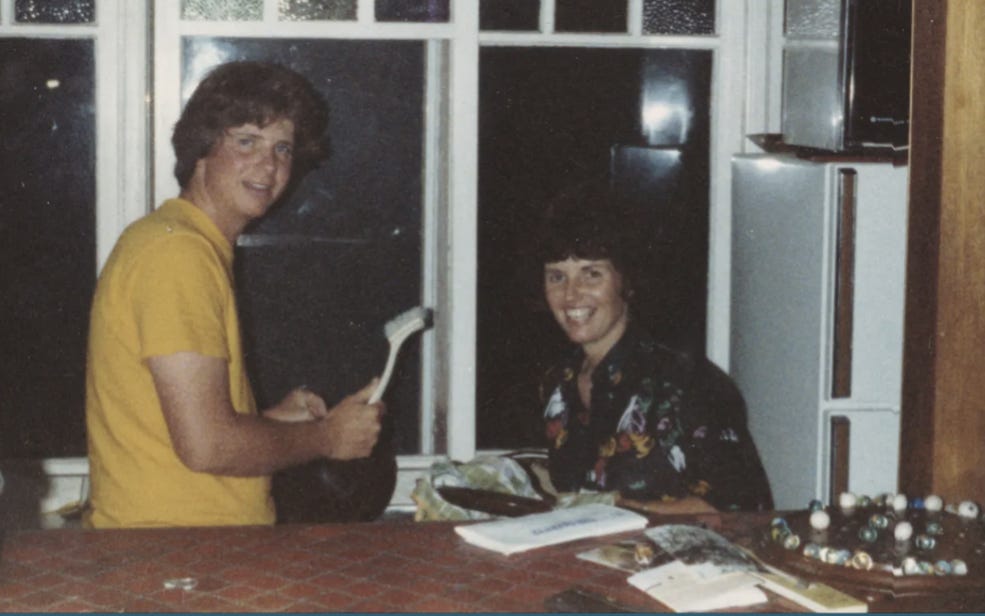

Luckily, an asteroid did hit me when I was chosen for that exchange program. I would finish my senior year of high school in Cronulla, a suburb of Sydney, Australia. My Aussie “parents” were Phil and Shân, who had immigrated to Australia from Wales more than fifteen years before.

I exchanged some letters with them and even chatted briefly on the phone.

Subscribed

When I finally landed in Australia and met Phil and Shân, they seemed completely different from my own parents and what I saw as their very conventional lives.

They’d immigrated to Australia, for one thing. Phil was an easy-going former airline mechanic turned milkman with a shaggy beard. And he rode a motorcycle! Meanwhile, Shân was a whip-smart, energetic, no-nonsense woman with very strong opinions.

The day after I arrived, Phil took me for a walk on the nearby beach. “So,” he asked me, “what do you want out of your visit here?”

I didn’t know how to answer — partly, because I wasn’t used to being asked what I wanted. The truth is, the life I wanted seemed so unattainable it wasn’t worth dreaming about.

I was able to tell him one thing I wanted: to lose weight.

“Okay,” Phil said. “Let’s see what we can do about that.” Somehow he said it in a way that didn’t make me feel bad about myself.

After that, he and Shân invited me on their evening walks. “Come on then, Michael!” Shân would say. “Let’s go!”

They also encouraged me to explore the rocky shore by myself.

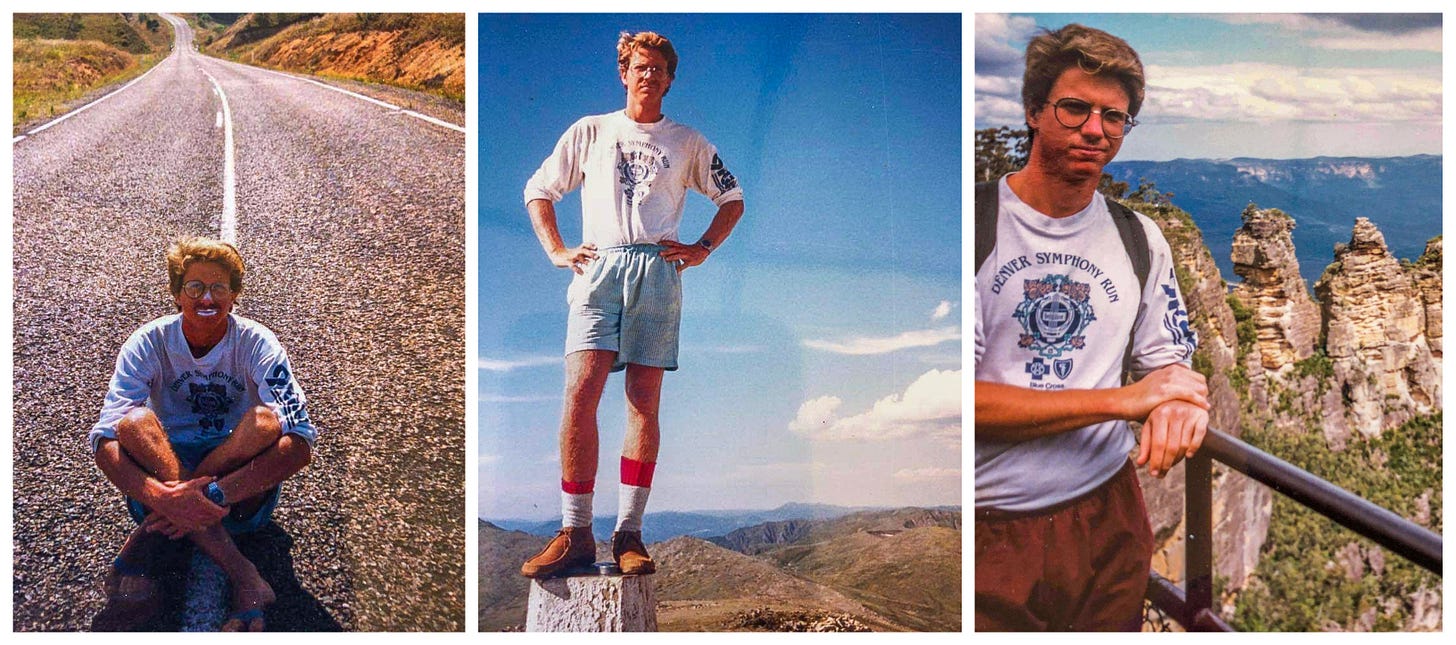

The ocean frightened me — I definitely wasn’t adventurous — but Phil taught me how to bodysurf, which I absolutely loved. I started going for morning swims in the rock pool just below our house and even took up snorkeling.

To my amazement, I started to lose weight.

But this was the least of it.

One day, Phil asked, “Do you want to learn how to ride a motorcycle?”

I knew my parents would flip if I took a risk like that. And I was scared. Motorcycles were fast and loud and dangerous.

But I’d loved bodysurfing and snorkeling. Plus, I liked the idea of being someone who, you know, rode a motorcycle. Because overweight bookworm Michael would never do anything like that.

I went and had a great time. On another outing, Phil taught me to shoot a gun. Once, several of the other exchange students suggested four of us go camping in the Blue Mountains — without any adults. Phil and Shân said sure, which amazed me. Wasn’t camping without adults reckless and dangerous? I went and had a blast — and no one died.

Eventually, I told Shân my dream of becoming a writer. She didn’t act like the idea was ridiculous or tell me it was a foolish choice.

“If that’s what you want,” she said, “then you should do it. But just talking about it won’t make it happen.”

As I said, Shân was no-nonsense.

Over dinner another night, I talked about how much I didn’t want to go back home. That doing so meant I’d end up like my parents — my American ones, that is. I hated the idea of a 9-5 job and living in the suburbs.

“I think I might even want to live outside of America,” I said.

“Then you should,” said Shân.

“But my parents will be so angry.”

“Why?” asked Phil.

I thought for a moment, then said, “Because they’ll think I’m rejecting them and the way they live.” Which was true: I was rejecting them.

“It’s fine if a conventional life isn’t for you,” said Phil. “But there isn’t anything wrong with it either.”

“You can’t be responsible for how they feel about your life,” said Shân. “And you have to live your life the way you want or you’ll end up very bitter. But you can be as considerate of their feelings as possible.”

Phil nodded. “You just have to decide what you want and then do that.”

I know now that giving thoughtful, unbiased advice is easier to do with other people’s children.

But I still appreciated it, the way Phil and Shân seemed to see me for who I actually was. It felt incredibly liberating — and a bit frightening. After all, people I respected had now given me permission to go after my dreams. If I didn’t follow through, I couldn’t blame it all on my parents.

If I can lose weight, I thought to myself, maybe I can do the rest as well.

Of course, change is never easy, and life doesn’t usually move in a straight line.

My first year of college, I regained most of the weight I’d lost in Australia. And, because my father insisted, I majored in business, a subject that I loathed.

But being hit by the “asteroid” that was Australia — and Phil and Shân — really did change my trajectory in the end.

Between my freshman and sophomore year, I joined a gym, determined to lose the weight I’d gained and more. Almost forty years later, I can say I’ve kept it off.

I graduated with that degree in business, but tossed it in the trashcan the moment they handed me my diploma, and promptly moved back to Australia where I backpacked around the country and got a job working at the World Expo in Brisbane.

Eventually, I landed in Seattle where I started my journey to becoming a writer. It’s also where I found the courage to finally come out, and I met my husband, Brent.

I’ve now been making my living as a writer for more than twenty years, though it hasn’t been easy. Maybe my parents had a point about that.

But they were wrong about almost everything else.

Remember how I started this? How I walked away from the edge of Australia’s Wattamolla Cliff — how I’d chosen not to jump.

There’s more to the story.

Yes, I walked away.

But I stopped again and thought about all I’d done in Australia — losing weight, riding a motorcycle, shooting a gun. I’d even gotten so drunk at a party, I’d wound up barfing in a bathroom. That might seem like a weird thing to be proud of, but it’s a teenage rite of passage the old Michael never would have done.

Then I turned around, walked back to the edge of the cliff, took a deep breath — and I jumped.

And I’m really, really glad I did.

Michael Jensen is a novelist and editor. For more about Michael, visit him at MichaelJensen.com.

I spent a couple of summers in Cronulla and did a rather large cliff jump which had thinking time during the time from the top to the bottom. I wonder if it was the same? Australia too changed my trajectory, but some years after this jump.

This is wonderful and it really resonates, as someone who has never quite fit into a traditional mold. Thank you!